I am not aware of when my father, Joan Oró, came to know Salvador Dalí. Both prominent Catalans, they likely knew of each other's work. Possibly, they met in the late '60s or early '70s. Nevertheless, at some point, Oró asked Dalí if he would create artwork for two scientific meetings planned for June 1973 in Barcelona, Spain. Dalí agreed.

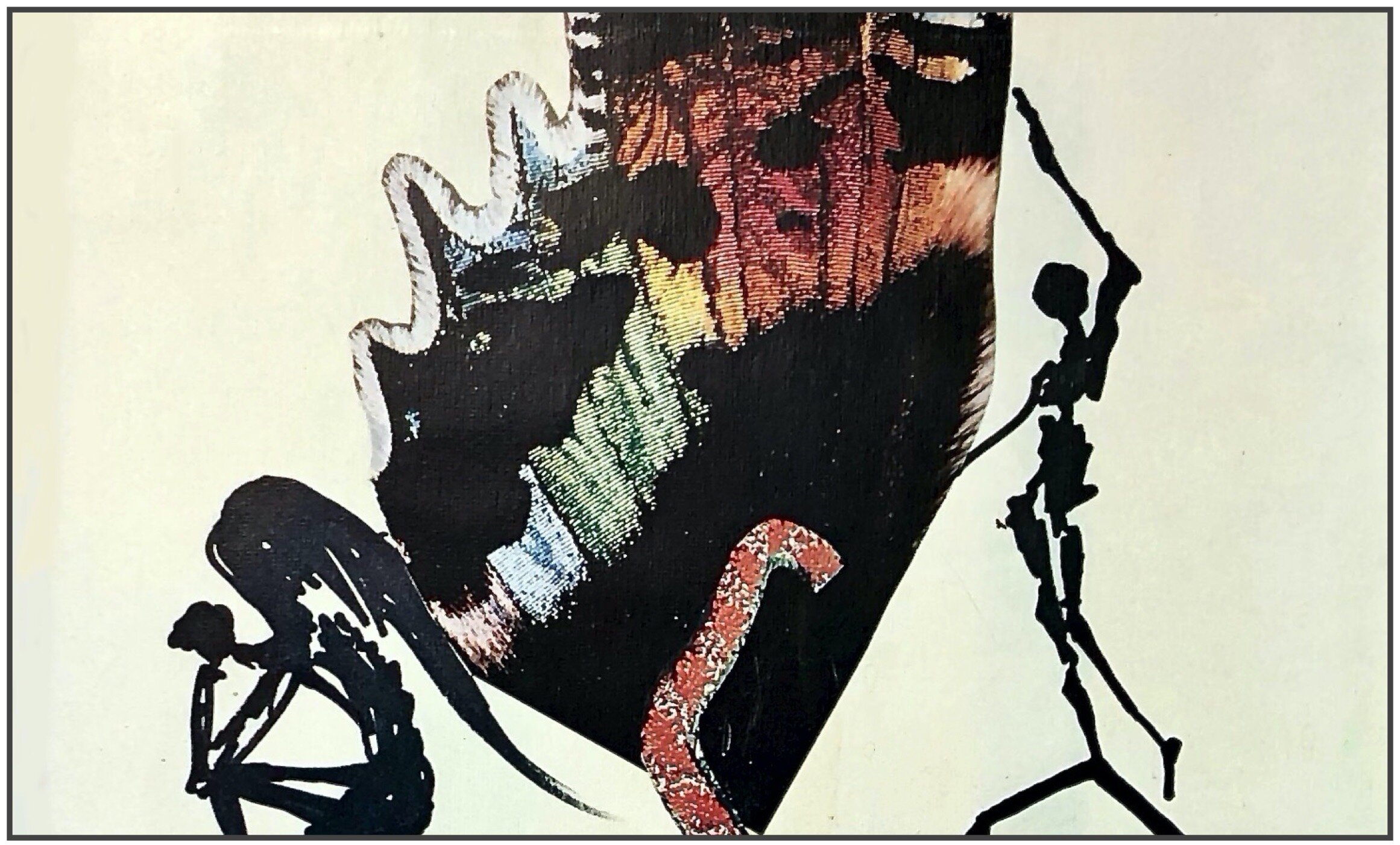

The resulting mixed media piece is stunning in its execution and insight. Containing only eight elements, it succinctly encapsulates the origin of life on Earth, the only known life in the universe.

Professor Joan F. Oró

To understand the artwork, a bit of background on the life of Joan (John) Oró. (Catalan pronunciation of Joan.) Born in 1923 in Lleida, Spain, Oró obtained his degree in chemistry, with a focus on organic chemistry, at the University of Barcelona in 1947. He married Francesca the following year and over the next five years, the couple had three children: Maria Elena, Joan (this author), and Jaume.

Together with colleagues, Oró established a series of small chemical manufacturing businesses that produced soap, chemicals for the pharmaceutical industry, and antiseptics. Each business was challenging. Not wanting to request more funding from the family, his childhood dream of studying the origin of life began to re-awaken. Given the confined nature of science in Spain during that era, Oró knew he would have to move. He submitted over 50 applications to universities throughout the US. Of the six schools accepting him tuition-free, Joan selected Rice Institute in Houston and moved to the US in 1952.

Partway through his first year at Rice, Oró met prominent Baylor College of Medicine scientist Donald Rappaport and was recruited into Baylor's Ph.D. program. There, he immersed himself in biochemical research that would become fundamental to his later discoveries in life's origin.

Following his training at Baylor, Oró joined the University of Houston as a professor of biochemistry in September 1955. In January 1958, he was able to bring his family to the US, where the couple's fourth child, David, was born.

Origin of Life Research

In 1959, Oró was working to extend the experiments by Stanley Miller in Harold Urey's lab at the University of Chicago. Miller and Urey’s studies had revealed that organic matter, specifically amino acids, could arise from a non-organic pre-biotic soup. This demonstrated that inorganic matter, in the right conditions, could turn into organic matter, the matter of life. Influenced by his understanding of cometary composition, Oró had added additional compounds to the mix. As described in ABC CIENCIA:

On Christmas Day 1959, Oró performed an experiment in his laboratory that would be crucial to the study of the origin of life. With the intention of reproducing the conditions that existed on Earth 4 billion years ago, Oró exposed to heat and ultraviolet light a solution that contained hydrogen cyanide and other chemical compounds that are usually present in comets. The chemical reaction he induced in his laboratory produced amino acids, the basic "bricks" of proteins, as predicted by current theories.

The surprise was that in that chemical reaction was also synthesized adenine, one of the four chemical bases that make up DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), the molecule of life.

Since the production of adenine, a nucleic acid within our DNA, was beyond what Oró considered possible, he thought it must have been a contaminant. Upon rigorously repeating the experiment, there it was again! A bright spot on the chromatograph at the precise position of adenine. It would be one of the happiest moments of his life.